WHAT’S OLD IS NEW AGAIN

Foley Machine Shop Salvages Parts, Saves You Money

Ever hear the term “throwaway society”? It’s the idea that we live in a culture that uses items once, then tosses them aside when they’re no longer working. Most of us are probably guilty of that, to some extent.

Ever hear the term “throwaway society”? It’s the idea that we live in a culture that uses items once, then tosses them aside when they’re no longer working. Most of us are probably guilty of that, to some extent.Not Drew Deever and his team at Foley Equipment’s full-service machine shop in Topeka, Kansas. Their entire business model is built on repairing and restoring worn or broken machine parts. Some of what they’re able to fix — and the time and money it could save — might surprise you.

“We can salvage about 80-90% of what comes through our shop,” Drew says. “On some projects, we can save the customer tens of thousands of dollars by salvaging a part versus buying new.”

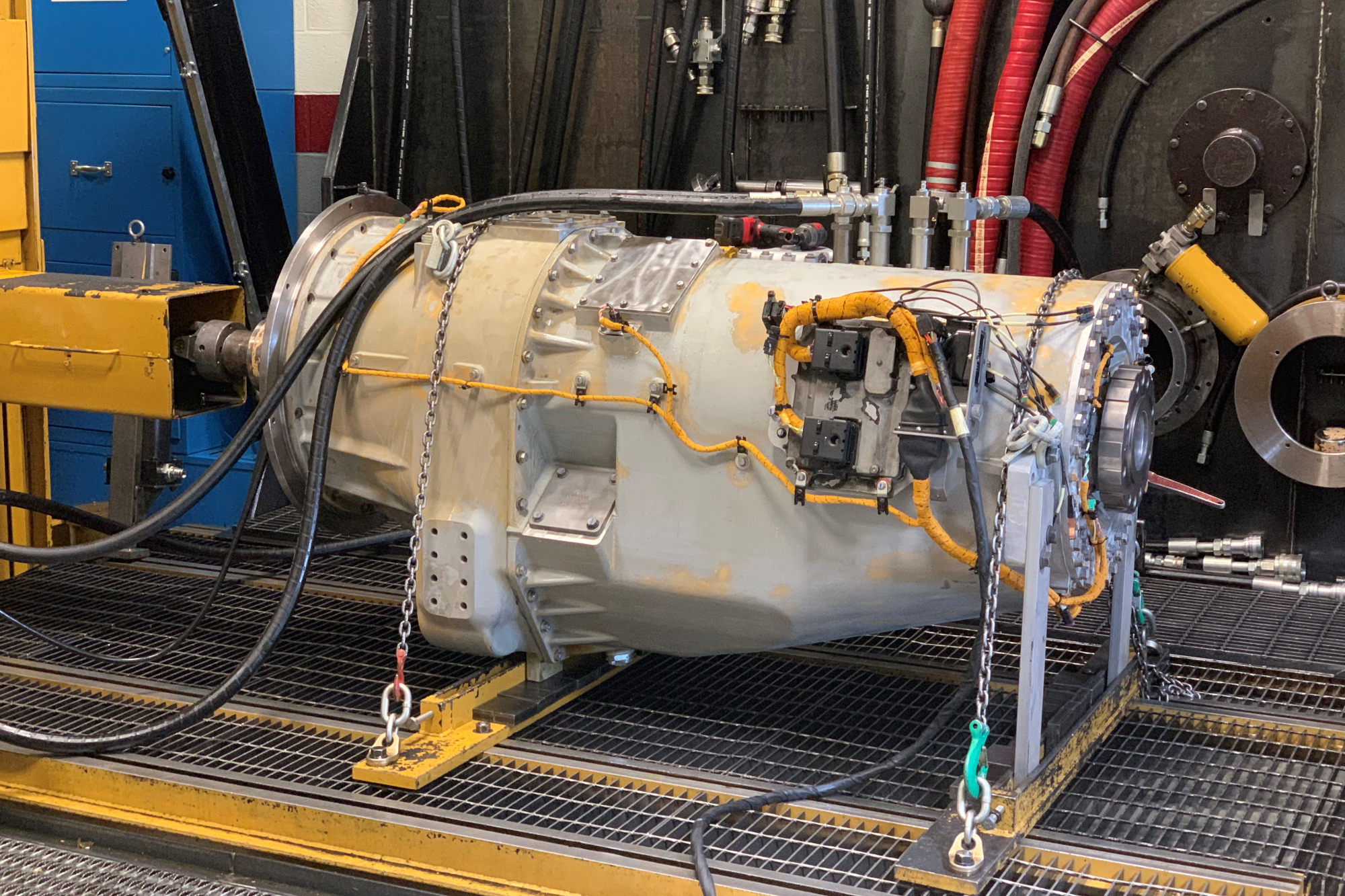

Damaged, not destroyed

What exactly can the machine shop salvage? Almost any part found on a piece of heavy equipment, barring brake and steering components that can’t be restored for liability reasons. That includes everything from blocks and bearings to cylinder rods and barrels to linkage pins and cutting edges.

In most cases, it costs significantly less to salvage these components than to replace them with new parts.

In most cases, it costs significantly less to salvage these components than to replace them with new parts.“I can honestly say there have not been that many parts we haven’t been able to fix,” Drew says — and he should know. He’s worked in the shop since 2001, taking on the role of manager in 2015.

The list of services Drew and his team offers is lengthy, too: Welding. Custom fabrication. Lapping and grinding. Bore reconditioning. Lathe work. Shaft repair. Vertical milling. Even portable line boring performed on a customer’s jobsite.

“Typically, we weld a part and re-machine it back to the size it was when it was new,” Drew says. “If a part can’t be welded, we can use metalizing, which involves spraying metal powder on the part at a very high temperature to give it a hard surface, then re-machining it.”

Whatever the process, every component gets restored to original Caterpillar dimensions and tolerances, ensuring it performs as expected inside the machine.

“We’ve built a very good reputation by proving that we can fix parts, that they work and that they’re cost-effective,” Drew says. “We’ve even had other Cat® dealers send us work, because they know our capabilities.”

“We’ve built a very good reputation by proving that we can fix parts, that they work and that they’re cost-effective,” Drew says. “We’ve even had other Cat® dealers send us work, because they know our capabilities.”Any age, any brand — repaired fast

Common repairs underway inside the machine shop include equalizer bars on dozers and bucket linkages on loaders and excavators. But Drew and his team also serve a lot of customers running older Cat models, who rely on them to fabricate obsolete parts. And some customers don’t operate Cat equipment at all.

“We’ll take whatever comes in the door,” Drew says. “We retrofit a lot of Cat parts onto non-Cat machines — bucket edges, linkage assemblies, undercarriage.”

Because the machine shop is centrally located within Foley’s service territory, turnaround time is usually quick — ranging from a single day for smaller repairs to two or three weeks for larger projects. Having both machining and welding expertise in the same facility is a bonus.

“It’s a time savings for sure,” Drew says. “We can do the machine work right along with the weld work. They go hand in hand.”

For uncommon parts that ship from overseas, salvaging is almost always a faster solution.

“During the pandemic, when supply chain was an issue, we were able to salvage a lot of parts that weren’t readily available,” Drew says. “We were able to get customers back on the job quicker.”

A century’s worth of knowledge

Unlike other machine shops, which focus more on fabricating parts in large quantities, Drew and his team perform machining that’s much more specialized. In addition to salvaging parts for customers, they serve as the dealership’s centralized component rebuild shop. They also make tooling, jigs, racks, teardown stands and other equipment to support Foley’s tool room and service technicians.

Unlike other machine shops, which focus more on fabricating parts in large quantities, Drew and his team perform machining that’s much more specialized. In addition to salvaging parts for customers, they serve as the dealership’s centralized component rebuild shop. They also make tooling, jigs, racks, teardown stands and other equipment to support Foley’s tool room and service technicians.“We’re not just putting metal in a machine and pushing a button,” Drew says. “What we do is not automated, and it takes a lot more skill.”

That requires an expert team, and Drew’s got that in spades. His experience combined with that of his nine employees — six machinists, two shop welders and one field welder — totals more than 100 years on the job. New technicians pair up with veterans for on-the-job mentoring and training.

Every team member brings excellent mechanical skills to the job, along with a host of intangible qualities — everything from out-of-the-box thinking to good hand-eye coordination to a stick-to-it mentality. They also understand how Cat parts work together as a system.

“If one part’s worn out, we know that you’re probably going to see wear in certain other areas as well,” Drew says. “We can address that contingent damage that you may not even see yet.”

Saved from the junk heap

For Drew, who studied accounting in college but ultimately decided he wouldn’t enjoy a career sitting behind a desk, salvage work is a rewarding business.

For Drew, who studied accounting in college but ultimately decided he wouldn’t enjoy a career sitting behind a desk, salvage work is a rewarding business. “When I first started working here, it was intimidating to see the size of the parts being repaired,” he says. “But that accomplishment of salvaging something, putting it back in the machine and seeing it run as good as new — that’s just awesome.”

“When I first started working here, it was intimidating to see the size of the parts being repaired,” he says. “But that accomplishment of salvaging something, putting it back in the machine and seeing it run as good as new — that’s just awesome.”So awesome, in fact, that he’s been applying some of his on-the-job expertise in his personal life. Drew and his dad rebuilt a 1995 Chevy several years ago and are finishing up work on a 1957 model now.

“It was basically just a shell on a frame when we bought it — we had to do everything,” Drew says. “Hopefully we’ll be driving it this summer. Dad decided to sell the ’55, but this one might be my inheritance, he keeps telling me.”

Passing it on versus sending it to the junkyard — that’s a legacy to be proud of.